Judge reduces lawyer's fees because of typos

A federal judge in Philadelphia, in prose suggesting barely suppressed chortles, reduced a lawyer's request for fees last month because his filings were infested with typographical errors.

The lawyer, Brian M. Puricelli, had offered this vigorous but counterproductive defense:

"Had the defendants not tired to paper plaintiff's counsel to death, some type would not have occurred. Furthermore, there have been omissions by the defendants, thus they should not case stones."

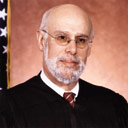

The judge was amused. But he was not moved. "If these mistakes were purposeful," Magistrate Judge Jacob P. Hart ruled, "they would be brilliant."

His decision was first reported in The Legal Intelligencer, a Philadelphia newspaper.

In the time-honored legal tradition, Magistrate Hart supported his ruling with evidence. "We would be remiss," he wrote, "if we did not point out some of our favorites."

In one letter, Mr. Puricelli had given the magistrate's first name as Jacon, not Jacob.

"I appreciate the elevation to what sounds like a character in The Lord of the Rings, " Magistrate Hart wrote, "but, alas, I am only a judge."

In all of Mr. Puricelli's filings, moreover, he identified the Federal District Court in Philadelphia as the United States District Court for the Easter District of Pennsylvania.

But the magistrate was quick to add that in many ways Mr. Puricelli is a terrific lawyer, at least when he is on his feet at a trial.

"Considering the quality of his written work," the magistrate wrote, "the court was impressed with the transformation. Mr. Puricelli was well prepared, his witnesses were prepped, and his case proceeded quite artfully and smoothly."

Indeed, Mr. Puricelli won the case he tried before Magistrate Hart. He represented John DeVore, a former Philadelphia police officer, in a civil rights case against the city and several of its officials. Mr. DeVore said he had been fired in retaliation for reporting that his partner had stolen a cellphone. The jury awarded him $430,000, which Magistrate Hart reduced to $354,000.

The law under which Mr. DeVore sued allowed him to recover his legal expenses, too, and Mr. Puricelli sought more than $200,000. The defendants objected, saying the quality of the work had not been worth $300 an hour.

Magistrate Hart agreed, in part, awarding $150 an hour for the time Mr. Puricelli spent writing legal papers. Never mind the typos, he wrote. Mr. Puricelli's prose was "vague, ambiguous, unintelligible, verbose and repetitive."

"Mr. Puricelli's complete lack of care in his written product shows disrespect for the court," Magistrate Hart wrote. "Mr. Puricelli's lack of care caused the court and, I am sure, defense counsel, to spend an inordinate amount of time deciphering the arguments."

He reduced Mr. Puricelli's fee by $31,500, to $173,000.

Mr. Puricelli, in a telephone interview, said he regretted the mistakes but considered them minor.

"There was no intention to be disrespectful to the court," he said.

On the same day Magistrate Hart issued his decision, a Utah appeals court judge chastised another lawyer for textual malfeasance.

The judge, Gregory K. Orme, wrote in a dissent in a zoning case that he had been persuaded of the plaintiff's position in spite of rather than because of its filings. He chastised the plaintiff's lawyer, Stephen G. Homer, for his "unrestrained and unnecessary use of the bold, underline, and all caps functions of word processing or his repeated use of exclamation marks to emphasize points in his briefs."

"While I appreciate a zealous advocate as much as anyone, such techniques, which really amount to a written form of shouting, are simply inappropriate in an appellate brief," Judge Orme continued. "It is counterproductive for counsel to litter his brief with burdensome material such as "WRONG! WRONG ANALYSIS! WRONG RESULT! WRONG! WRONG! WRONG!"

Mr. Homer declined to comment.

Bryan A. Garner, the editor of Black's Law Dictionary and the president of LawProse, a legal-writing consulting firm, said courts are becoming increasingly impatient with many lawyers' substandard writing skills.

"Lawyers are the most highly paid professional writers in the world," he said. "It's a good thing for judges to be more demanding."

By Adam Liptak

The New York Times, 2004-03-04